Looking back to my college days, I remember my undergraduate thesis—a collection of short stories about taking a trip to the capital.

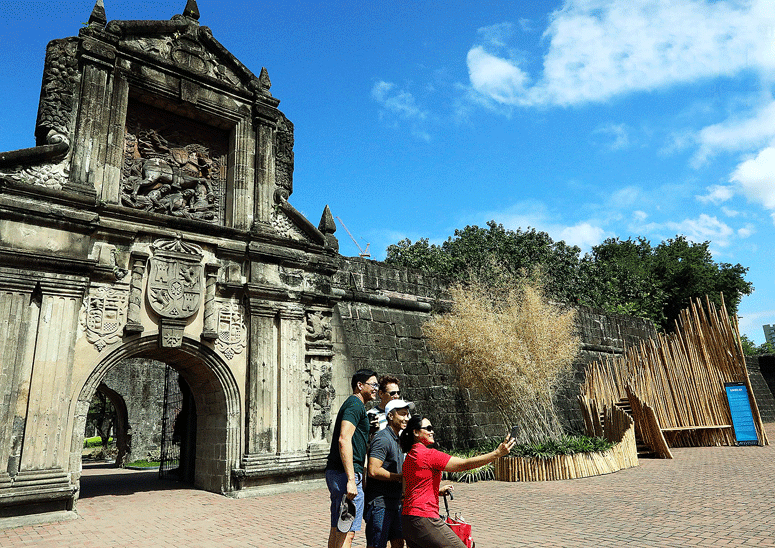

My favorite story was that of a girl who found herself trapped in Fort Santiago in Intramuros, Manila—leading to a sudden jump through time—with spirits of the dead haunting her.

The underlying point of the short story talked about the identity crisis of Filipino architecture. The girl was confused about the fort’s drastic changes even if the spirits reminded her that every restoration reflects the growth of Manila.

One of the most well-known historical sites in the Philippines is Fort Santiago. The citadel was once a palisaded fort armed with bronze guns, owned by Rajah Matanda. It was destroyed during the Spanish occupation, then rebuilt as Fuerte de Santiago in 1571.

Seeking the identity of Filipino architecture

A country’s historical sites are inspired by its cultures and traditions. But when you’re asked to describe the overall identity of Filipino architecture, it can be very tricky.

Some would describe it as being heavily influenced by the 300-year Spanish colonization, citing the City of Manila. Others would say it reflects the country’s economic growth through the years.

A key example of this is Ayala Avenue in Makati, a 1.9-kilometer road that crosses through the Makati Central Business District.

The country’s architectural landmarks are born out of evolving cultures and various events throughout history.

Unfortunately, the slow death of our these landmarks is perhaps a sign of our fragility as a nation.

Preserving our local heritage

Cultural writer Bambi Harper wrote that we are slowly erasing our history by having little to no regard for the country’s historic landmarks. Paying attention to development is a must for every state, but we’ve set our sights on growing economically that we’ve lost sight of the country’s identity in the process.

The City of Manila is just the tip of a disintegrating iceberg. We see historical sites demolished, replaced or now overshadowed by towering condominiums.

Imus, the de jure capital of Cavite, is also a product of our country’s identity crisis. What used to be the location of the Battle of Alapan and Battle of Imus is now replaced by houses, shopping malls, and business establishments.

The Imus City Hall on Maestro G. Tirona Street is one of the few facets left of the city’s colorful history.

An example of our country’s unique heritage can be seen on the torogan, a traditional house of the Maranaos in Lanao Province. Translated as “sleeping place” or “resting place,” it’s one of the things that establishes the identity of the Maranaos.

Deputy Mayor Gapor Usman Al-Haj describes the torogan as one of the qualities of the Maranao’s cohesiveness as an indigenous group in a 2017 interview.

And it’s indeed a sight worth admiring once the pandemic ends. One of the house’s key features is its wing-like extensions adorned with detailed floral and animal carvings called okir.

The okir is another unique part of the Maranaos’ identity. If you’re curious about its design, take a look at the Sarimanok, a legendary figure in Philippine mythology.

Losing our country’s sense of self

The past decades have proven that time is not our friend when it comes to preserving the identity of our local heritage. Another recent heartbreaking news is the old Philam Life Building in Ermita, Manila being dismantled. The photos became viral on social media as netizens signed petitions to stop its demolition.

Many people name newly built roads, schools, hospitals and buildings after historical figures in honor of their legacy. But is this enough to fix the identity crisis in terms of our local heritage?

When you travel through EDSA, does it remind you of historian and journalist Epifanio de los Santos? No, the stressful traffic and hellish commute are what come to mind.

There are various calls to preserve the country’s past by restoring the structural integrity of historical sites and buildings. Unfortunately, it’s going to take a lot of political will and a deep understanding of our local heritage for this to happen.

American author Michael Crichton said that not being aware of history is like a leaf that doesn’t know which tree it comes from. We’re slowly becoming leaves that just go through the motions of our everyday lives, forgetting where we came from.

As for the girl in my short story, she was able to return to the present. She walks out of Fort Santiago in a confused daze. Unfortunately, that’s where her trip ends, still stuck in an identity crisis.