Growing up in different houses — renting tiny homes until there were five children in the family — I understand the struggle of low-income families in finding a safe and decent home.

National Economic and Development Authority (NEDA) Acting Secretary Karl Kendrick Chua reported recently that there are 18 million low-income Filipino families. A 2018 study of the Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS) classified families earning a monthly income of below P10,957 as “poor,” P10,957 to P21,914 as “low-income but not poor,” and P21,914 to P43,828 as “lower middle.”

In a general sense, “low-cost housing” is a misnomer because it covers housing projects costing P1.7 million to P3 million, which minimum wage earners certainly cannot afford.

The more appropriate ones are “economic housing” ranging from P450,000 to P1.7 million, and “socialized housing” costing P450,000 or below.

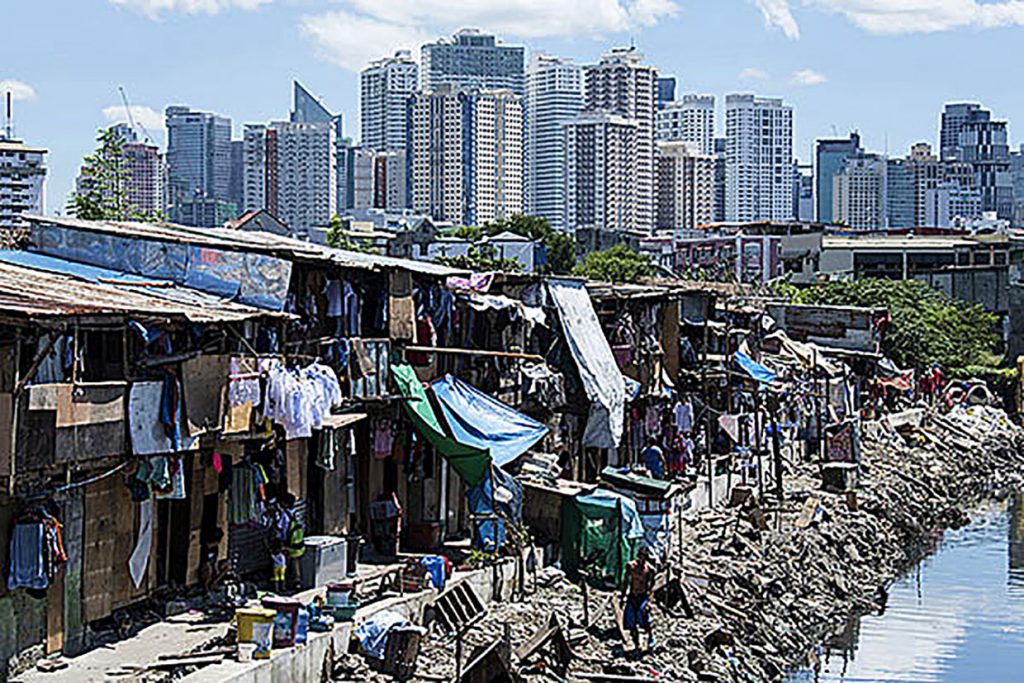

According to the Chamber of Real Estate and Builders’ Associations Inc. (CREBA), the housing backlog is at 6.57 million units, with the gap between supply and demand increasing 300,000 units annually.

Looking back at the 18-million figure of poor households, it’s lamenting that there could be far more families looking for basic adequate shelter, not to mention the many layers of insecure tenure.

On a global scale, “the United Nations once estimated that 10 million people worldwide die each year from conditions related to substandard housing,” according to Habitat.org.

“More than 20 percent of the world’s population struggles, on a daily basis, to stay in houses or on land where they live, and more than 80 percent of the world’s population does not have legal documentation of their property rights.”

In the Philippines, the creation of the Department of Human Settlements and Urban Development (DHSUD) (Republic Act No. 11201) in 2018 orders that the state shall undertake, “in cooperation with the private sector, a continuing program of housing and urban development which shall make available at affordable cost, decent housing and basic services to underprivileged and homeless citizens in urban centers and resettlement areas. It shall also promote adequate employment opportunities to such citizens.”

This new law should therefore challenge the existing condition and process of socialized housing.

Despite its lowered housing price, such units often remain empty; or homebuyers change their minds and go back renting at in-city dwellings. Worse, some add up to the number of informal settlers in slum areas. This is because the housing projects fail to address some social services and the additional costs of transportation to and from the residents’ sources of livelihood.

In his article titled Ensuring the affordability of socialized housing: Towards liveable and sustainable homes for the poor that appeared in UP CIDS Policy Brief last year, Chester Antonino Arcilla provided critical policy recommendations for the government and the private developers engaged in creating off-city resettlement, namely:

(1) Develop a housing affordability indicator/s that incorporate the effects of relocation on post-relocation household net incomes;

(2) Provide income-based subsidies for the poor and institute income-restoration mechanisms;

(3)Recognize affordable and decent in-city housing as a significant component of a comprehensive poverty reduction program;

(4)Institutionalize participatory governance for the urban poor at the national, local and institutional levels;

(5) Institutionalize alternative tenure modalities within an equitable and inclusive urban land reform; and

(6) Develop a clear and integrated framework on employment generation based on equitable urban and regional agricultural development.

What is affordable housing? The United Nations Human Settlements Program (2011) defines it as “adequate in quality and location and does not cost so much that it prohibits its occupants from meeting other basic living costs or threatens their enjoyment of basic human rights.”

CREBA meanwhile is urging the Bureau of Internal Revenue to suspend the imposition of VAT on low-cost housing.

Under the TRAIN law, residential lots worth up to P1.9 million and house-and-lot units up to P3.2 million are exempt from VAT until December 31 this year. By 2021, only those worth P2 million and below would be exempt.

As someone in the lower-middle income bracket who wishes to buy a bigger home, this spells another economic crisis for me. But if the imposition of VAT pushes through, let’s hope the government uses the additional funds to at least augment the poor’s housing loans.